Katie has lived on Vancouver Island all her life. She has a husband, Niki, and two daughters. Their family loves spending time outdoors, whether it’s kayaking, hiking, or spending the day at the beach.

A genetic blood disorder called hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) runs on Niki’s side of the family. Part of the disorder is characterized by the malformation of blood vessels—including vessels in the brain. For Niki, his mother, and his grandmother, the condition only ever manifested in more frequent nosebleeds than experienced by the average person. Katie never thought the condition would put her then nine-year-old daughter Autumn at risk for something far more serious.

On December 7, 2020, Katie was already at work, and Niki was still asleep when Autumn came into their bedroom to tell him she had a headache. Then, she experienced what looked like a seizure, and began vomiting. Niki rushed Autumn to Nanaimo Regional General Hospital, where he learned his daughter had an arteriovenous malformation (AVM)—an abnormal tangle of blood vessels connecting arteries and veins—in her brain, which had ruptured.

Autumn was then airlifted to BC Children’s Hospital.

“We didn’t know if she would walk or talk again,” says Katie. “With brains, you just don’t know. There was the thought that her life might be over.”

Autumn stayed in the hospital for nearly a month. At the end of December, she was moved to Sunny Hill Health Centre, a rehabilitation facility. There, she spent the next four months learning how to walk, talk, and eat again before she was finally able to return to her home in Nanaimo and go back to school with the support of an Education Assistant.

As a result of her traumatic brain injury, Autumn suffers from spasticity—a neurological disorder that creates a high resistance to movement—in her left arm, which was curled up to the point where she could no longer extend it. It also affected her left leg and caused some difficulty walking.

“Autumn was receiving Botox treatments every three months at Sunny Hill for her spasticity. The Botox was not fun, and all of those needles were really painful,” says Katie. “It would deaden the muscle so that her arm could stretch out again, but she still couldn’t use it. It wasn’t helping her arm work again.”

Autumn’s physician at Sunny Hill thought she might be a good candidate for a ground-breaking treatment for those living with spasticity, and referred her to see Dr. Paul Winston, Island Health’s Medical Director of Rehabilitation and Transitions at Victoria General Hospital.

Autumn and her sister, Hazel

“When we first went to see Dr. Winston, we were in the waiting room and Autumn kept saying she was scared,” says Katie. “But there was an older woman in the waiting room with us, and she told us that she couldn’t walk two months ago, and thanks to Dr. Winston she was now walking with the help of a walker.”

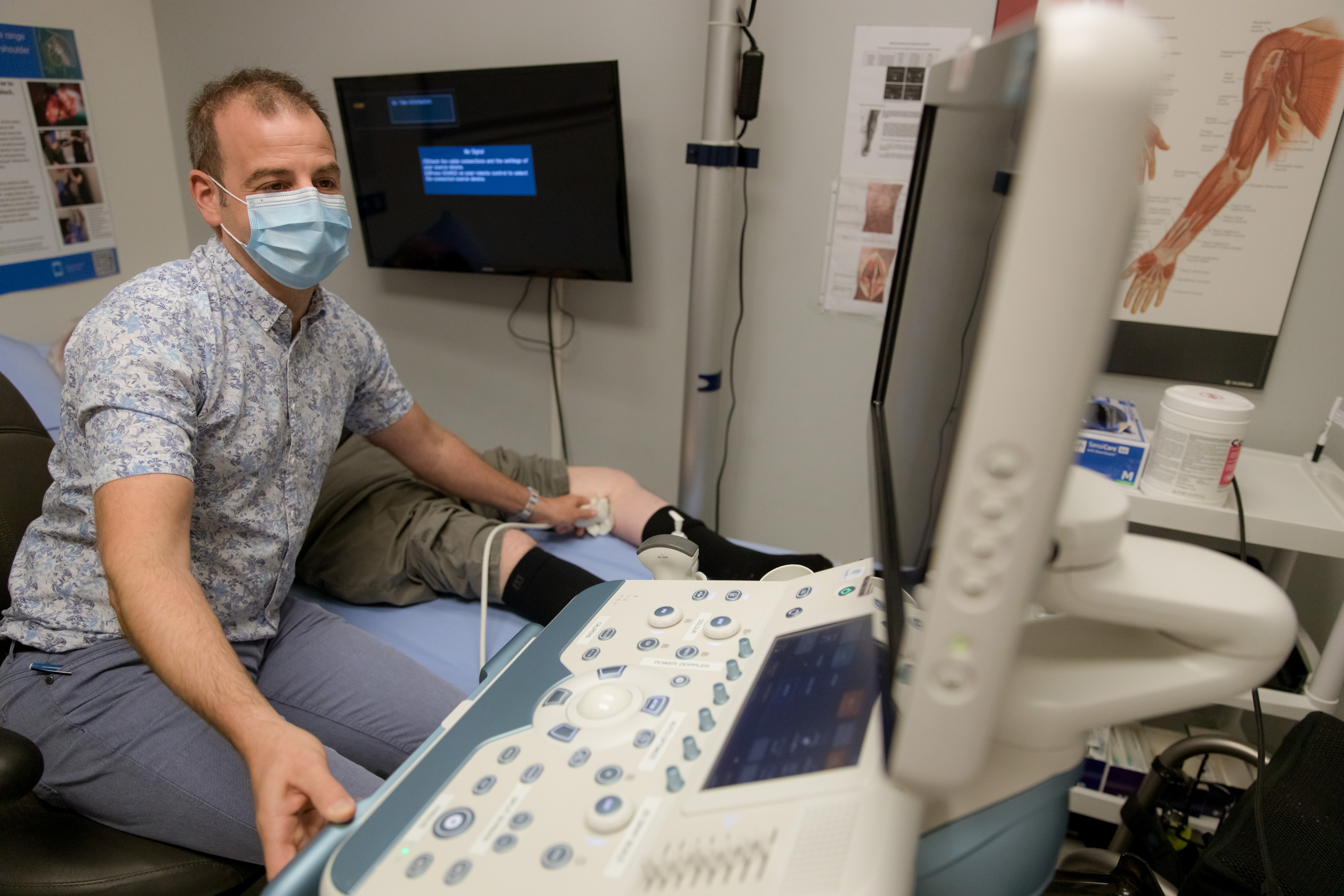

Dr. Winston treated Autumn’s left arm and a few spots in her leg by inserting a tiny probe with nitrous oxide gas to deep-freeze the nerves that were causing her muscles to contract and tense up. He used a physiatry ultrasound to help locate which nerves to freeze.

Immediately, Autumn was able to begin to stretch out her arm and move her fingers for the first time since December 2020.

Today, Autumn is able to use her hand, and can grasp and let go of objects. Her walking has also improved, and she’s limping less. She still does speech therapy to help with her short-term memory problems, but Katie says she continues to get better.

“She has come so far. We’re pretty hopeful that she will have full use of her arm again through the nerve-freezing treatments,” says Katie. “Autumn is really happy about being able to use her arm and hand again, and she loves going to see Dr. Winston.”

When Autumn first met Dr. Winston, she was the youngest patient in the world to ever receive his nerve-blocking treatment for spasticity. The novel use of this technology was designed by Dr. Winston and his team in Victoria, and, as far as they know, it is the only treatment of its kind in the world. The team is now working to present the procedure across North America, Europe, and beyond, with the hope that it will become a global practice.

“This is going to be life-changing for Autumn. It will be the difference between whether or not she can drive one day,” says Katie. “She’ll still have some social issues and things like that—but she’s here, and that’s what’s important.”